The Classiscam scam-as-a-service program has reaped the criminal actors $64.5 million in illicit earnings since its emergence in 2019.

"Classiscam campaigns initially started out on classified sites, on which scammers placed fake advertisements and used social engineering techniques to convince users to pay for goods by transferring money to bank cards," Group-IB said in a new report.

"Since then, Classiscam campaigns have become highly automated, and can be run on a host of other services, such as online marketplaces and carpooling sites."

A majority of victims are based in Europe (62.2%), followed by the Middle East and Africa (18.2%), and the Asia-Pacific (13%). Germany, Poland, Spain, Italy, and Romania accounted for the highest number of fraudulent transactions registered in Classiscam chats.

First discovered in 2019, Classiscam is an umbrella term for an operation that encompasses 1,366 distinct groups on Telegram. The activities first targeted Russia, before spreading its tentacles worldwide, infiltrating 79 countries and impersonating 251 brands.

The attacks took off in a big way during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 driven by a surge in online shopping.

Group-IB told The Hacker News that Classiscam is the same as Telekopye, which was chronicled by Slovak cybersecurity company ESET last week as a phishing kit used by cyber criminals to create fake pages from a premade template.

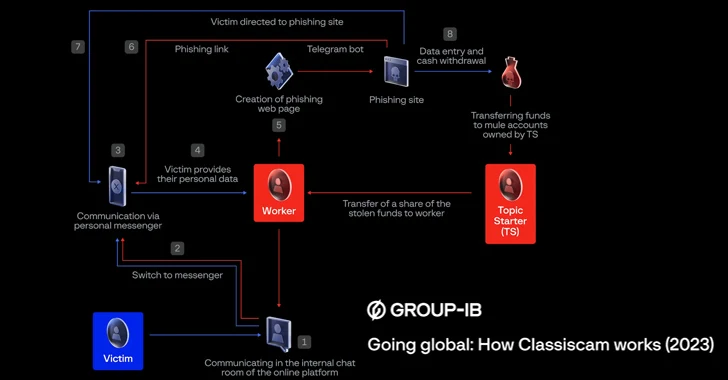

Among the methods employed by cybercriminals to carry out the scheme is to trick users into "buying" the falsely-advertised goods or services via social engineering schemes and directing potential victims to the automatically generated phishing websites.

This is accomplished by moving the conversations to instant messaging apps so as to ensure that the links don't get blocked. The phishing pages are created on the fly using Telegram bots.

Campaigns targeting a subset of countries also include fake login pages for local banks. The credentials entered by unsuspecting victims on these pages are harvested by the scammers, who then log in to the accounts and transfer the money to accounts under their control.

Classiscam operators can play the role of both buyers and sellers. In the case of the former, the actors claim that payment for an item has been made and deceive the victim (i.e., the seller) into paying for delivery, or entering their card details to complete a verification check via a phishing page.

The backend infrastructure that facilitates the scam is an intricate pyramid of workers and bombers, who interface with the victims and redirect them to the spoofed pages; supporters; money mules; developers; and administrators, who oversee the recruitment of new workers and other day-to-day aspects.

"Classiscam operations have evolved over time and different tactics, techniques, and procedures have been introduced," the Singapore-based cybersecurity company said.

"In some of the most recent Classiscam operations [...], the scammers added a balance check, completed by the victim, to the phishing web pages. This step was introduced so that the scammers can assess how much money is in the victim's bank account to understand the amount they can charge to the card."

A significant change in the modus operandi of some of the groups involves the use of stealer malware to collect passwords from browser accounts and transfer the data. Group-IB said it identified 32 such groups that switched from carrying out traditional Classiscam attacks to instead launching stealer campaigns.

As stealer families become more robust, multifaceted, and accessible, they not only lower the barrier to entry into financially motivated cyber crime, but also act as a precursor for ransomware, espionage, and other post-compromise mission objectives.

The findings come as a new United Nations (U.N.) report revealed that more than 200,000 people in Southeast Asia, particularly Cambodia and Myanmar, are being coerced by organized criminal gangs into participating in romance-investment scams (aka pig butchering), crypto fraud, and illegal gambling.

Some victims have been subjected to forced labor, sexual violence, torture, cruel punishments, and arbitrary detention, among other crimes, it said. The scams are estimated to have generated billions of U.S. dollars every year.

"Most people trafficked into the online scam operations are men, although women and adolescents are also among the victims," the U.N. Human Rights Office said.

"Most are not citizens of the countries in which the trafficking occurs. Many of the victims are well-educated, sometimes coming from professional jobs or with graduate or even post-graduate degrees, computer-literate and multilingual."